Amazon's Latest Grocery Push: Mapping the Battle for Online Grocery Delivery

Amazon’s latest grocery delivery expansion cements its ambition to be a full-spectrum player. But the bigger story is how competing fulfillment models are reshaping the economics of online grocery.

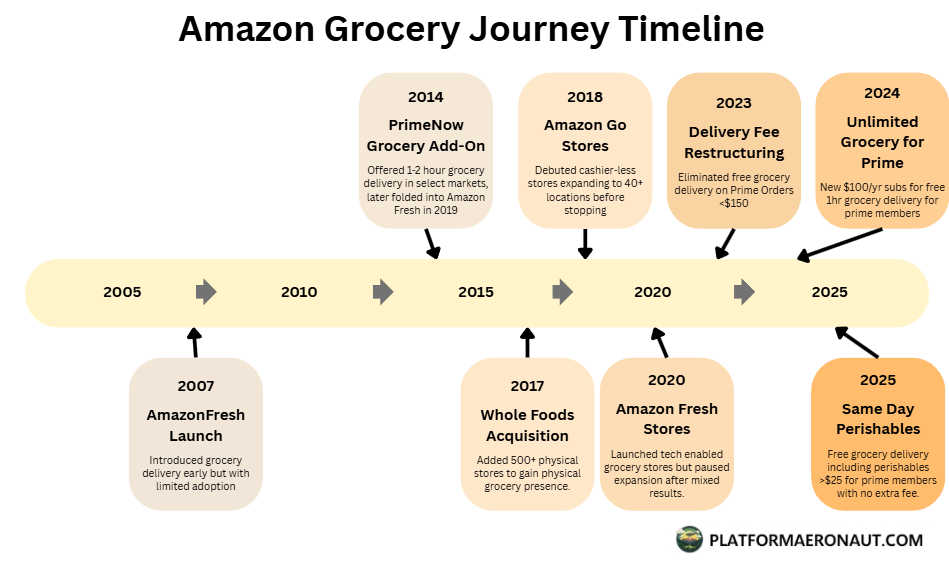

Amazon just announced a massive expansion of its same-day grocery delivery and is now offering perishable items like produce, dairy and meat in over 1,000 cities with plans to scale to 2,300 by YE25. Rather than the mishmash of Whole Foods, Amazon Fresh, and Amazon.com with various subscriptions and pricing, they’ve streamlined it under one umbrella with free delivery for Prime members >$25.

Amazon’s grocery strategy is no longer exploratory. With blended in-store, dark-store, and rural delivery investments with integration under one umbrella, the company is cementing it’s focus to be a dominant, full-spectrum grocery provider going against Walmart and Instacart. The big question is whether Amazon will be successful with this or whether it’ll be another misstep in their long desired goals in grocery delivery.

Given the big changes I figured it would be valuable to do a primer on grocery delivery models, competition, and unit economics.

Grocery Delivery Strategic Models

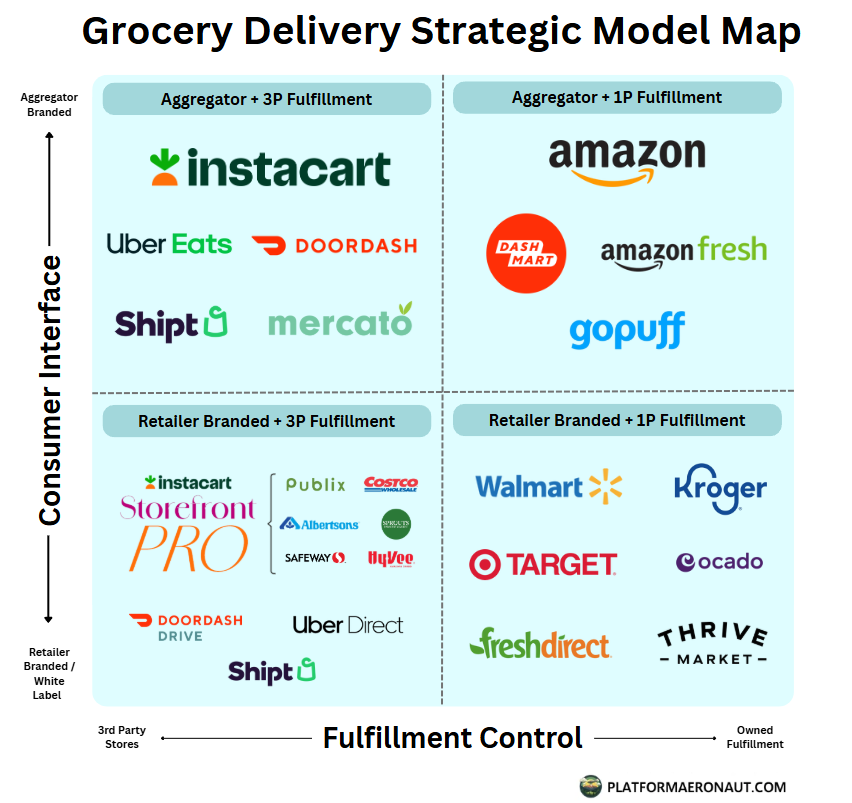

The online grocery landscape can be charted on a quadrant defined by who owns the consumer interface (aggregator vs retailer-branded) and who controls fulfillment (3P stores vs 1P fulfillment). I’ve mapped out the major players in the US market into the four quadrants below.

Aggregator + Third-Party Fulfillment (Marketplace Model)

In this model, an aggregator platform owns the customer relationship and leverages third-party retail stores for inventory and fulfillment. Companies like Instacart, Shipt, DoorDash, and Uber Eats exemplify this approach. Here, a customer places an order through the aggregator’s app or website for items sold by a local grocery retailer. The aggregator then dispatches a personal shopper or courier to pick items off the partner store’s shelves and deliver them to the customer’s door.

The appeal of the marketplace model is its asset-light scalability. Aggregators don’t need to own inventory or stores because they tap into existing grocers’ shelves as virtual warehouses. This allowed Instacart and others to rapidly scale across thousands of stores and cities, essentially piggybacking on retailers’ infrastructure. It’s a win for consumers in terms of convenience and selection (multiple grocer options in one app) and for smaller retailers who instantly get an online channel without heavy investment.

However, the trade-offs are significant. Because the aggregator is a middleman taking a slice of the transaction, margins are slim and unit economics are challenging until scale is achieved. Instacart’s commission (roughly a 6% take-rate, about $7 on a $110 order) is only about half the percentage that food delivery apps like DoorDash take for restaurant orders. Grocery baskets are larger, so that 6% still yields comparable dollars per order, but the operations cost is high. The retailer keeps the majority (~85% of the sale) to cover the product cost and store costs, meaning both the store and the platform are splitting an already thin retail margin. Aggregators like Instacart have found that massive order volume and density are required to turn a profit in this model – CEO Fidji Simo noted they “used to lose money on every order until we got to 100 million orders” delivered, underscoring that scale is everything.

From the retailer’s perspective, participating in these platforms is a double-edged sword. On one hand, they gain incremental online sales and new customers they might not reach otherwise. On the other, they relinquish direct customer relationships and some margin to the aggregator (many grocers privately gripe that Instacart can feel like a “necessary evil” siphoning off profit). Over time, the major aggregators have started to improve economics by layering on high-margin revenue streams like advertising.

Aside from Instacart, which leads the U.S. market for large-basket grocery delivery, other players follow a similar model with some twists. Shipt, owned by Target, operates a marketplace app and also powers Target’s same-day delivery (more on that below). DoorDash and Uber Eats originally built their networks on restaurant delivery, but they have expanded into groceries by partnering with chains like Walgreens, Albertsons, or smaller grocers on their apps.

Overall, the Aggregator + 3P quadrant is characterized by fast deployment and wide reach, but with tight margins and reliance on retailer partnerships. The strategic calculus for aggregators is to grab market share and leverage scale (and ads) to eventually drive profits, while retailers in this model often view it as a customer acquisition channel or an interim solution as they develop their own capabilities.

Aggregator + Owned Fulfillment (Vertically Integrated)

This quadrant involves an aggregator or marketplace that operates its own fulfillment infrastructure, essentially playing the role of the retailer by owning inventory and distribution. The prototypical example is Amazon, which has invested heavily in its first-party grocery fulfillment through Amazon Fresh warehouses and the acquisition of Whole Foods Market. Other examples include rapid-delivery startups like Gopuff, and initiatives by delivery platforms (e.g. DoorDash’s DashMart dark stores). The strategy here is to marry the branding and demand aggregation of a platform with the control of end-to-end logistics.

In Amazon’s case, it leverages its massive logistics network and customer base to deliver groceries under the Amazon brand. Amazon Fresh centers and Whole Foods stores act as its own “warehouses.” By owning the inventory, Amazon captures the full retail markup on products (there is no grocer taking ~85% of the basket as in the Instacart model). It also has flexibility in product selection and pricing and can ensure availability of specific items. Importantly, vertical integration allows for operational efficiencies like batching deliveries, implementing automation, and optimizing fulfillment centers solely for delivery.

The challenges, of course, are the heavy fixed costs and complexity. Running grocery warehouses and delivery fleets is capital-intensive. Amazon has learned that online grocery is a different beast given the previously mentioned challenges. The vertically integrated aggregator model bets that owning the supply chain will pay off in superior customer experience and eventually better margins once scale is achieved and costs are spread out.

Quick Delivery / Rapid Delivery Specialists

Specialized players like Gopuff take a more focused approach: stocking convenience and snack items in small urban fulfillment centers and offering delivery in 20-30 minutes. Gopuff essentially acts as both the retailer and the delivery platform for quick-need items. The trade-off, however, is that Gopuff must build a network of dozens of micro-fulfillment centers and maintain inventory, which is cash-intensive. The company expanded rapidly during the pandemic, then had to retrench in 2022–2023 as demand normalized and investors demanded profitability. The jury is still out on whether this model can scale sustainably in markets beyond dense cities

Aggregator Owned Dark Stores

Traditional delivery apps have also dabbled in this space: DoorDash’s DashMart is a good example of an aggregator adding owned fulfillment. DashMart locations are essentially DoorDash-owned convenience stores (dark stores) carrying a selection of grocery staples, prepared foods, and local products. DoorDash saw the success of the Gopuff model and the value of being able to fulfill orders even when a third-party merchant isn’t involved (capturing more margin per order and ensuring supply).

Overall, the Aggregator + Owned Fulfillment quadrant is a higher risk/reward strategy. The upside is greater control over the customer experience and potentially better margins per order (no revenue split with a retailer; you earn retail markup). Many vertically integrated services have struggled to achieve positive unit economics, especially when they promise ultra-fast delivery: the costs of courier labor, small basket sizes, and promo discounts can outweigh the margins.

Retailer-Branded + Third-Party Fulfillment (Outsourced E-commerce)

In this quadrant, the retailer maintains the customer interface and brand, but much of the heavy lifting of online fulfillment is outsourced to third-party services. This is a common path for traditional grocery chains that want to offer delivery or pickup without building all the technology and logistics from scratch. The most prominent example is grocers partnering with Instacart’s white-label services.

With this arrangement, a customer might order directly on a grocery chain’s website or app (seeing the retailer’s branding and prices), but the order is actually fulfilled by Instacart in the background. Instacart’s shoppers pick the items and deliver them, and Instacart provides the software infrastructure. Many regional and mid-sized grocers have used this model: for instance, Publix, Costco, Albertsons, Safeway, Hy-Vee, and others have offered delivery via their own sites with “Powered by Instacart” behind the scenes.

Another flavor of this model is retailers using third-party delivery couriers for last mile while managing the ordering and picking themselves. For example, a supermarket might have its own employees pick online orders from the store, but then hand off to services like DoorDash Drive or Uber Direct. In all these cases, the customer’s transaction is with the retailer’s brand but a third party handles execution.

The strategic appeal here is that retailers keep ownership of the customer relationship and data. They control the front-end experience, loyalty program integration, and pricing. The retailer essentially “rents” the fulfillment capabilities of specialized 3P players. The downside is cost and dependency. Third-party fulfillment isn’t cheap given these providers charge fees or take a cut of sales, which often erodes the already slim margin on groceries. There’s also the strategic risk of becoming reliant on an external tech platform. Many grocers are wary of Instacart’s growing power; if a large share of their customers get accustomed to ordering via the Instacart-powered channel, the retailer might feel like Instacart “owns” those customers anyway. This is partly why some supermarkets that initially outsourced everything have been investing in taking parts of the operation back in-house over time.

Despite these concerns, the retailer+3P model remains prevalent. It’s a pragmatic compromise for many: you get to offer online shopping and stay in the game, but you essentially pay a toll to the experts to help fulfill it. Over time, we’ve seen more nuanced partnerships emerge. Instacart itself now pitches a suite of enterprise services beyond shoppers, and also powers grocers’ websites, analytics, and even advertising programs. This indicates that the model is evolving from just gig labor provisioning to a broader outsourced e-commerce platform role.

Retailer-Branded + Owned Fulfillment (In-House Model)

In the final quadrant, the retailer takes full ownership of the online grocery operation. This is typically pursued by the largest, most resource-rich grocers who view digital grocery as a core, strategic part of their business (and who have the volumes to justify big investments). Walmart is the poster child here, having built up a massive grocery pickup and delivery operation on the back of its thousands of stores. Kroger also fits, especially with its recent build-out of automated fulfillment centers via Ocado despite poor performance there.

The retailer in-house model’s biggest advantage is control and integration. The retailer can design the online experience exactly as it wants, integrate with its stores and supply chain, set its own fees/pricing, and keep 100% of the sales margin (there’s no third-party taking a cut). In theory, if done efficiently, this model can slightly improve margins or at least avoid the margin leakage that happens with third-party fees. For instance, Kroger has suggested that a fully automated warehouse model (like Ocado) could improve the economics of online orders, and one estimate claimed a grocery order via an Ocado CFC could yield a 4-5% margin to the retailer, versus essentially 0-2% when using a third-party like Instacart.

Walmart’s Store-as-Fulfillment Strategy

Walmart’s approach has been to leverage its existing assets, where its huge store footprint doubles as a network of local fulfillment centers. Walmart invested in training their store associates to pick online orders from aisles, built intuitive apps for pickers, and implemented curbside pickup infrastructure and delivery services (first through partners, but increasingly through Walmart’s own Spark driver network). By using stores, Walmart avoids building all-new warehouses for most orders and can fulfill online demand from nearby inventory that’s also serving walk-in customers. This “stores-as-hubs” model has been quite successful in terms of adoption; Walmart quickly became the U.S. market leader in grocery pickup/delivery by volume.

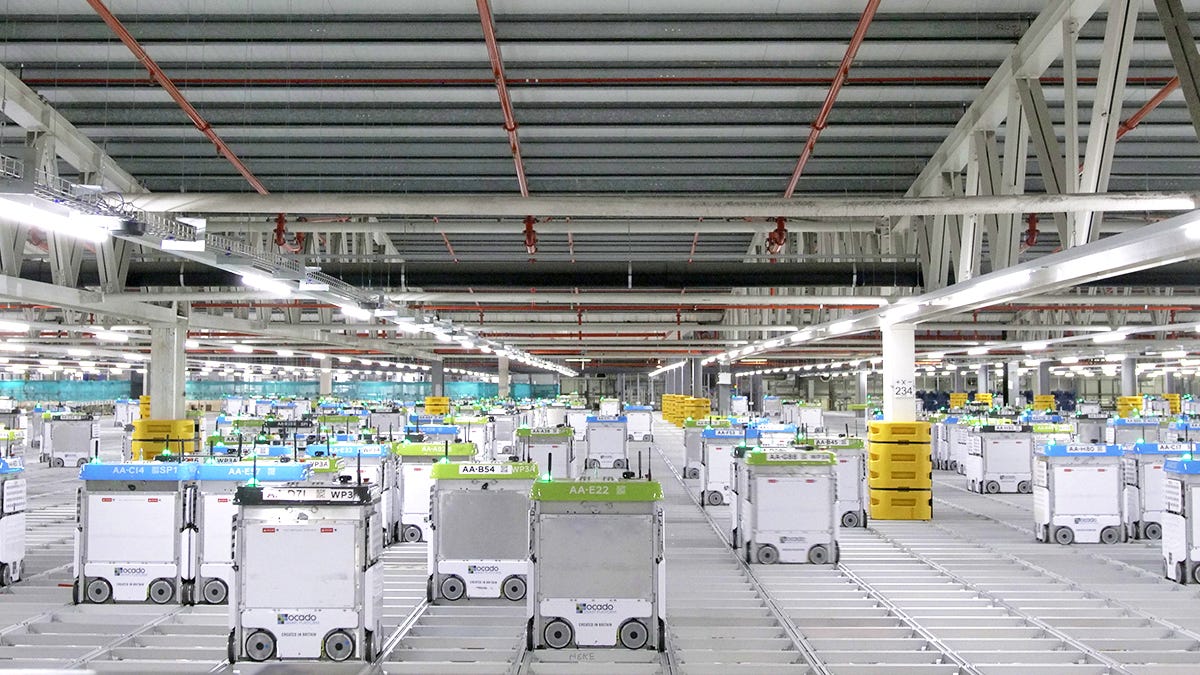

Kroger and Ocado’s centralized fulfillment

Kroger, lacking Walmart’s coast-to-coast store density, pursued a different in-house tactic: centralized fulfillment. Through a partnership with UK-based Ocado, Kroger is building a series of high-tech fulfillment centers for grocery delivery. These giant CFCs (Customer Fulfillment Centers) use automation (robots that shuttle bins of groceries) to pick orders with high efficiency and accuracy. The downside is longer lead times (orders are often next-day scheduled rather than same-hour) and the huge fixed cost of each facility means it only makes sense with significant volume. Early results have been mixed with Ocado struggling with deployment and financially.

Target’s Hybrid Approach with Shipt

Target essentially internalized a third-party model by buying Shipt. Target’s customers ordering same-day delivery see a Target interface and Target employees do in-store picking, but the delivery is handled by Shipt’s network (which Target owns). This way Target kept the operation largely in-house while still leveraging gig labor for the last mile.

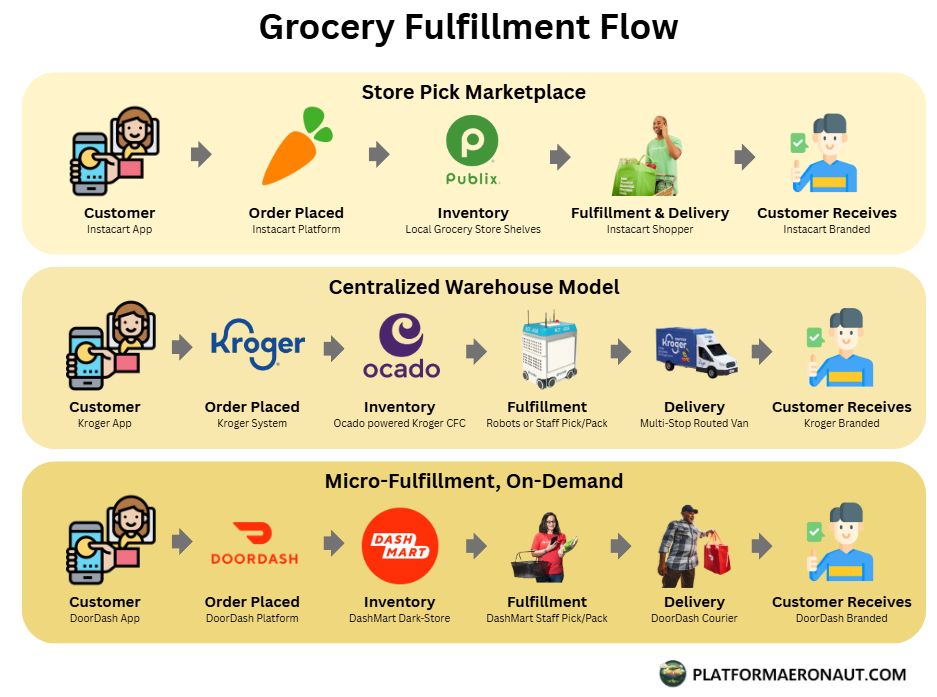

Grocery Fulfillment Architecture

The above diagram illustrates three primary models for how a grocery order travels from inventory to the consumer. . Each of these fulfillment architectures carries different cost structures, speed capabilities, and scalability challenges which directly impact the unit economics of each model.

Unit Economics by Fulfillment Model

Store-Pick Marketplace

The cheapest to set up (uses existing stores, no new capex), but the most expensive per order in labor. A gig shopper or store employee walking aisles might cost $7–10 per order in picking time, plus delivery costs of $6–10. It works at low volumes and enables rapid market entry, but margins are thin unless orders are batched. Grocery orders picked this way often leave the retailer breakeven at best, especially once fees to platforms like Instacart are included.

Centralized Warehouse / CFC

High upfront cost (tens to hundreds of millions per facility), but lower variable cost per order once scaled. Robots pick items more cheaply than humans, and delivery routes can be batched with dozens of orders per truck. A fully utilized CFC might bring fulfillment+delivery cost down to ~$8–12 per order vs. $15–20 for in-store pick, but if volume is low the overhead crushes economics. Better margin potential (target 3–5%) but only viable at large scale.

Micro-Fulfillment / Dark Stores (MFCs, DashMart, GoPuff)

A middle ground: small dedicated warehouses near customers with a curated assortment. Lower labor cost than store-pick (pickers don’t navigate crowded aisles), but higher overhead than using existing stores. Delivery costs remain high because baskets are smaller (often <$40) and couriers run orders one by one. Unless order density is very high, the unit economics are negative. When density is achieved, fulfillment cost per order can fall to ~$5–7, but delivery cost still dominates.

A Balancing Act

In conclusion, the grocery delivery infrastructure space is still in an evolving, strategic balancing act. No approach has a clear universal advantage; what works best often depends on the strengths and scale of the player. An aggregator like Instacart leans into scale and network effects (and now ads) to make an asset-light model profitable, whereas a giant retailer like Walmart leverages its physical footprint and accepts slimmer margins to defend its turf.

One thing is certain: scale and efficiency are paramount. Grocery delivery doesn’t have the luxury of high margins, so winning models will be those that turn logistical excellence and volume into a competitive edge. The grocery game is ultimately a high-volume, low-margin business, and that reality doesn’t change just because the order is online. Amazon will certainly have it’s work cut out for it as it attempts for the 5th or 6th time to get grocery right.

Tickers Mentioned: AMZN 0.00%↑ CART 0.00%↑ TGT 0.00%↑ DASH 0.00%↑ UBER 0.00%↑ WMT 0.00%↑

The information presented in this newsletter is the opinion of the author and does not reflect the view of any other person or entity, including Altimeter Capital Management, LP ("Altimeter"). The information provided is believed to be from reliable sources but no liability is accepted for any inaccuracies. This is for informational purposes and should not be construed as investment advice or an investment recommendation. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Altimeter is an investment adviser registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Altimeter and its clients trade in public securities and have made and/or may make investments in or investment decisions relating to the companies referenced herein. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not of Altimeter or its clients, which reserve the right to make investment decisions or engage in trading activity that would be (or could be construed as) consistent and/or inconsistent with the views expressed herein.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

Insanely good