AV Rideshare Fleet Sizing: Why the Optimum is Just Shy of Peak

An interactive model to pressure test optimal fleet size by MSA and city. Should AV fleets be sized to peak, average, or trough demand?

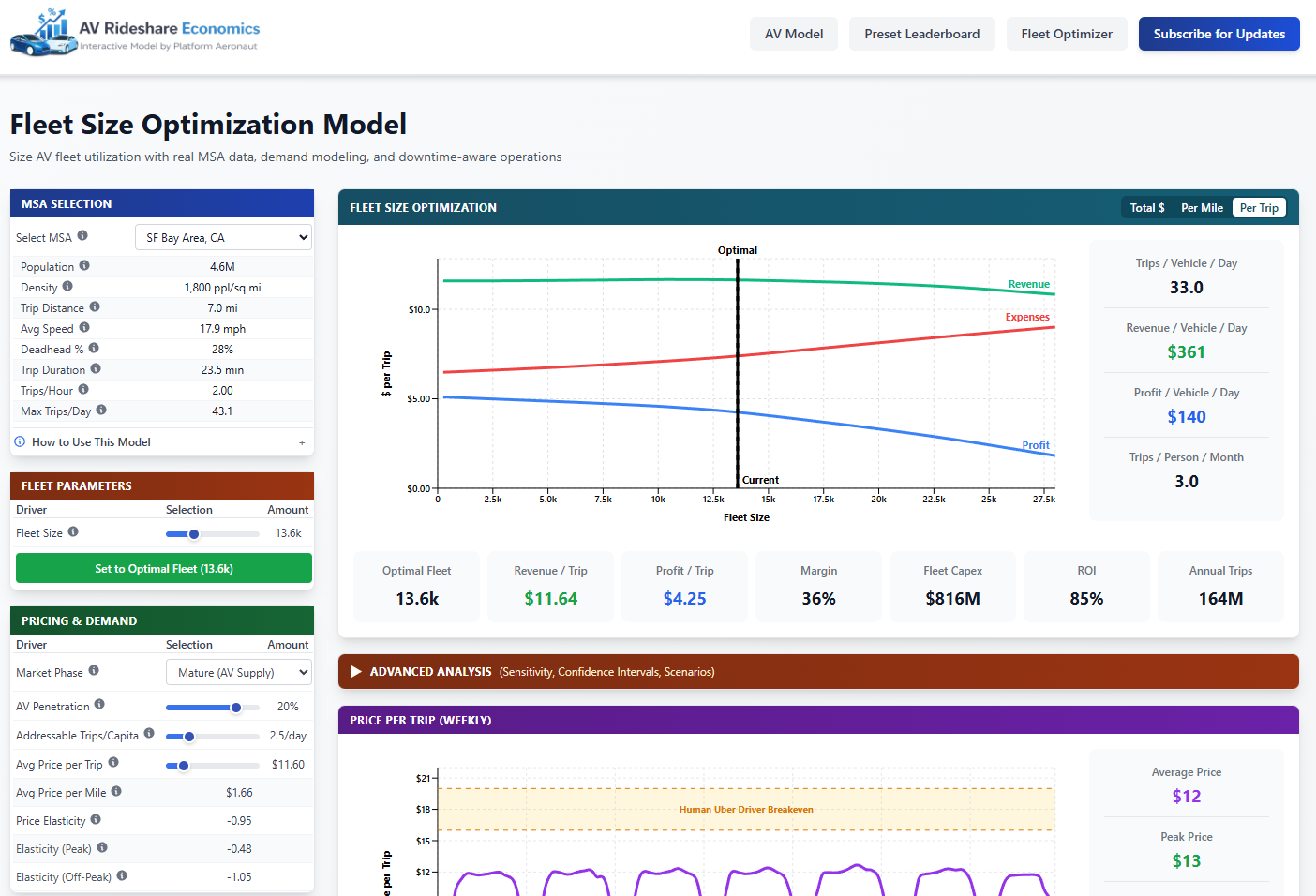

It’s not a question of whether autonomous vehicle ridesharing is coming, but a question of economics, scale, and sizing. I recently published AVRideshareEconomics.com that is an interactive model that tries to answer the question of “How profitable is AV ridesharing?” But the next logical question is “How big should an AV fleet be?”. For the default on AV Rideshare Economics I just plugged in 250k vehicles in the fleet but is that accurate or arbitrary? conservative or aggressive?

Bill Gurley has frequently asked the question of whether Waymo should build to peak demand or average? What makes economic sense? What is optimal from either an individual per ride basis or more importantly on a fleet-wide total profitability basis?

To answer that question I created a Fleet Optimizer within the website that is pre-populated with top 20 US cities/MSA data and computes based on population, density, trip distance and average speed among other variables. Below you can see the headline chart of optimal fleet size for cumulative top 20 MSAs in the United States that results in 319k vehicles:

In this model, “optimal” fleet size is defined as the point that maximuzes total fleet-level profit, not per-vehicle utilization and not per-ride margin.

High Level Conclusions:

Optimal AV fleet sizing is not peak demand, but it’s also not average.

For major MSAs, the economic optimum is 98-99% demand coverage

Oversizing fleets destroys pricing power faster than it increases utilization

National Top 20 MSAs imply ~319k vehicles, not millions

AV unit economics only work with aggressive off-peak price differentiation

The hybrid human+AV model matters most during ramp, not at maturity

Fleet Size Optimization Drivers

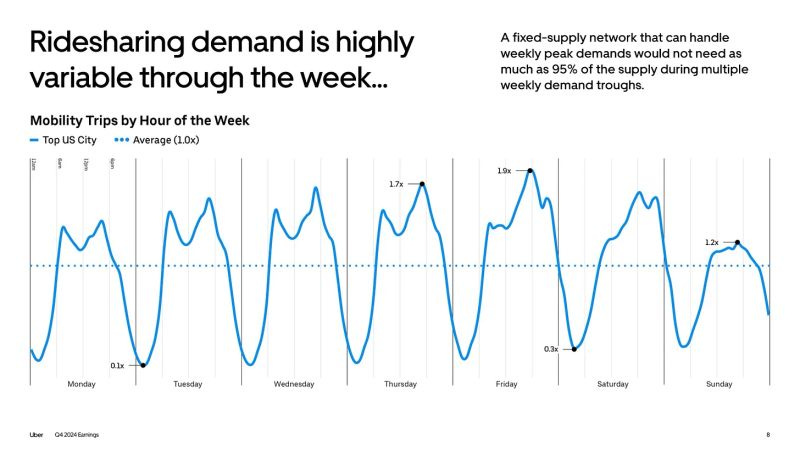

In creating this I worried most about garbage in - garbage out in terms of model drivers and how to arrive at reasonable assumptions to create a demand curve. I also utilized research studies, NYC and Chicago taxi/rideshare data, and the ridesharing demand variability chart that Uber posted in their earnings presentation a couple quarters ago:

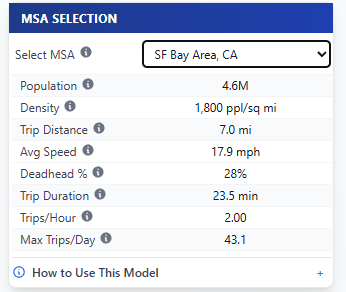

MSA Data

For each MSA I pulled down population, density, and other relevant statistical data and applied a regression against a variety of known data for Uber and Lyft rides today to spit out an average trip distance, driving speed, and deadhead % (time between trips). That provides an output for trip duration (23.5min for SF), trips per hour (2 for SF), and maximum trips per day (43.1).

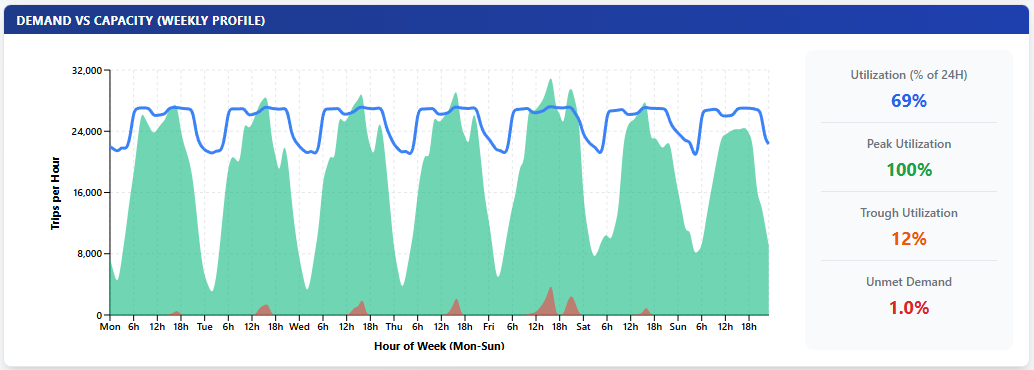

Pricing and Demand Curve

What is most challenging is building up that actual demand curve and applying the right price elasticity. You can’t just apply one price elasticity to all of ridesharing as consumer demand and elasticity differs over the course of a day. A rider at peak time versus off-peak versus normal periods has vastly different elasticity.

The reality for human drivers is that they naturally self select and match supply to demand because when demand is low at 2am most drivers are also at sleep. With an AV fleet that no longer naturally matches up supply with demand you need to have greater price differential in off-peak hours vs peak than you would with a human driver.

After a ton of research and adjustments I settled on price elasticities that feel right and are research supported for ridesharing.

Additionally in the model I set up three default market phases that affect pricing, penetration, and addressable trips per capita (as well as some of the cost levers). I’ve defaulted it to “Mature” which implies an addressable TAM of 2.5 trips per day per person and AV penetration of 20%. We are nowhere near that today with most cities at 2-3% penetration and high density metros at 5-8%. But in a world where AV rides might cost $10-12 perhaps 20% is possible. If that feels too aggressive to you there are “Early” and “Hybrid” defaults or you can change assumptions yourself.

Pricing vs Utilization Tradeoff

The central tradeoff in AV fleet sizing is between utilization and pricing power and it is fundamentally non-linear. At small fleet sizes adding vehicles increases utilization and captures unmet demand, but eventually once the fleet approaches full demand coverage incremental vehicles no longer create meaningful new trips, they simply reallocate demand across more idle assets. At that point utilization falls faster than volume rises, as incremental trips are spread across an expanding base of idle vehicles rather than concentrated on high-value hours.

The optimal fleet size is one that sits where nearly all demand is served, but scarcity still exists often enough to preserve price discipline.

Unlike human drivers, AV fleets do not naturally exit the market when prices fall, so oversupply persists and price becomes the only clearing mechanism. This is also why cost optimization alone cannot fix an oversized fleet. Once pricing power is lost, no reasonable reduction in depreciation, charging, or maintenance can restore profitability.

Costs

For the cost structure I generally kept the Mature market phase default matched up exactly with the default for the main AV Rideshare Economics model. For earlier phases I’ve scaled costs assuming less cost efficiency.

One note is that I also made a few changes to the main AV Rideshare Economics model:

I added in Taxes, Fees, and Tolls as a COGS to the model defaulted to 6% based on feedback received. This was a missing portion of the model beforehand.

Lifetime miles default I changed to 300k based on additional feedback and research I received.

Fleet Management cost defaults went up particularly around cleaning ($20/day) and parking/real estate ($100/mo) based on research and feedback.

Optimal AV Fleet Size for San Francisco Bay Area

So with the explanation of methodology and modeling out of the way what does it tell us about the optimal fleet size for autonomous vehicle ridesharing in San Francisco?

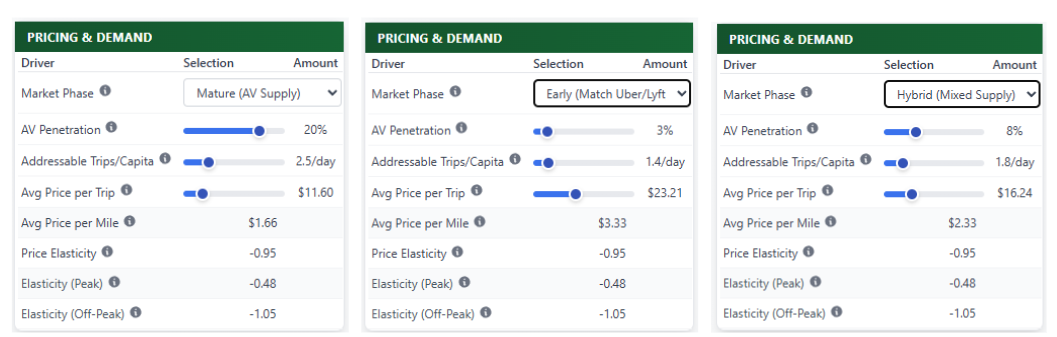

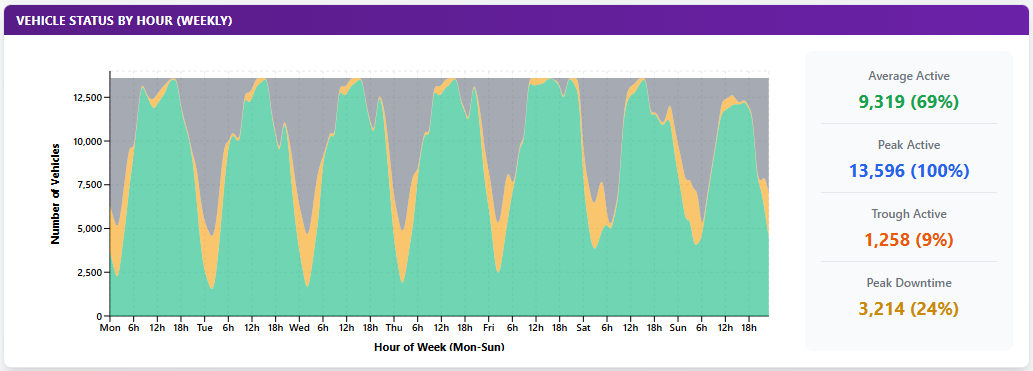

Based on optimizing total profitability, at maturity the optimal fleet size for AV ridesharing in the San Francisco Bay Area MSA is around 13,600 vehicles. Beyond that you start to get diminishing returns from underutilized vehicles and you also get hit with too many vehicles = overcapacity = pricing pressure. Over the course of a week though how does the demand vs capacity profile look like?

SF Bay Area Robotaxi Demand vs Capacity Weekly Profile

To answer Bill Gurley’s question of how to size a fleet, the answer is just shy of peak. If you optimize around having 1% of demand unmet and you can load charging, cleaning, maintenance, and downtime into off-peak periods then you are best served sizing your fleet to capture the vast majority of demand that exists.

To more accurately model this dynamic I had the model include active vs downtime vs idle vehicles by hour of day and allocate downtime to off-peak periods so that vehicles are available for as much peak demand as possible.

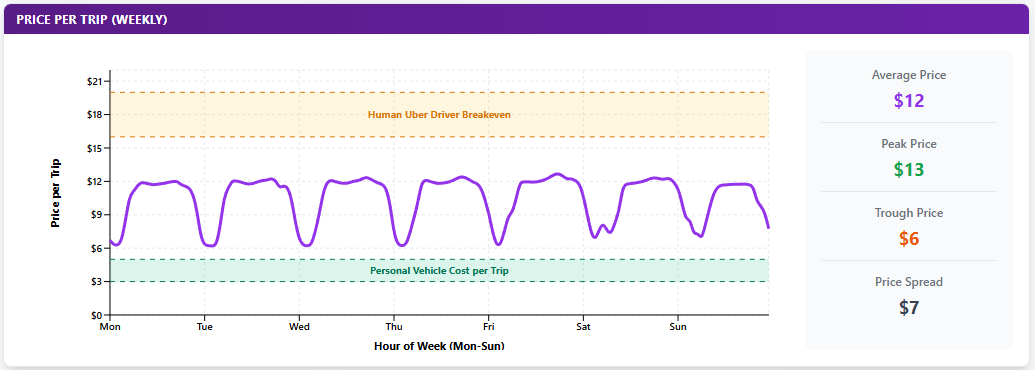

What about Pricing?

In this mature market phase scenario where does pricing sit? With an average price around $12 and trough around $6 you fall pretty squarely in the sweet spot for a fleet that Waymo or Tesla might run. Ideally you want your pricing below the above yellow line where human rideshare drivers breakeven. Below $16-18 per trip, a human driver will stop driving as it no longer makes financial sense.

It’s important to remember these are averages not absolutes and don’t encompass hyper-peak day activity or rain or snow or natural disasters that cause price spikes.

Who Wins: 1P vs 3P?

One conclusion is that fleet sizing logic favors operators who control pricing. Marketplaces that can dynamically blend human + AV supply are advantaged early. Fully autonomous 1P networks dominate only after scale and density.

Waymo’s recent fundraising rumors gives them the cash to fully pay for capex required to build out a US-wide network, but will they actually be able to replicate the scale and density required to be successful? We’re a long way from a mature market with >20% penetration of the ridesharing TAM and until we reach that point with at-scale costs and trips that cost 50% less than today, there’s a big disadvantage for a 1P only provider.

Will Autonomous Ridesharing Replace Personal Vehicles?

No, not in the short term. If you play with the pricing and cost levers of the model it’s almost impossible to see how Waymo or Tesla could reasonably charge $3-5 for an average trip to be equivalent to personal vehicle costs per trip. Even with optimistic assumptions around depreciation, maintenance, insurance, taxes/fees/tolls, and every other cost line item, you can maybe get cost per trip down to $6. The $3 robotaxi narrative is a fantasy under almost any realistic scenario.

The caveat I’ll make here is that there’s a scenario where a savvy operator could monetize their audience in other ways. If you price a ride at breakeven and let’s say in 5 years a ride structurally costs $5, how else could you make money? You could extensively advertise, do paid loyalty programs, or turn Waymo or Tesla into the Spirit Airlines of mobility with low base fares and upcharges for bags, priority, or amenities.

Fleet Optimizer Website: https://www.avrideshareeconomics.com/fleet-optimizer

The information presented in this newsletter is the opinion of the author and does not reflect the view of any other person or entity, including Altimeter Capital Management, LP (”Altimeter”). The information provided is believed to be from reliable sources but no liability is accepted for any inaccuracies. This is for informational purposes and should not be construed as investment advice or an investment recommendation. Past performance is no guarantee of future performance. Altimeter is an investment adviser registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Altimeter and its clients trade in public securities and have made and/or may make investments in or investment decisions relating to the companies referenced herein. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not of Altimeter or its clients, which reserve the right to make investment decisions or engage in trading activity that would be (or could be construed as) consistent and/or inconsistent with the views expressed herein.

This post and the information presented are intended for informational purposes only. The views expressed herein are the author’s alone and do not constitute an offer to sell, or a recommendation to purchase, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any security, nor a recommendation for any investment product or service. While certain information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, neither the author nor any of his employers or their affiliates have independently verified this information, and its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Accordingly, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to, and no reliance should be placed on, the fairness, accuracy, timeliness or completeness of this information. The author and all employers and their affiliated persons assume no liability for this information and no obligation to update the information or analysis contained herein in the future.

Excellent article. Love your theses on fleet sizing. I love that you’ve modeled specifically its Uptime. As these are new fleets, there will be a need to closely monitor how to get the fleets back in order when they go in for their maintenance.

I continue to think that Fleet sizes won’t win the near term play though they’ll win long term. I think it’s often easier to maximize the fleet success in one market before expanding too much